To understand the importance of Net Positive Suction Head Available (NPSHa) and Net Positive Suction Head Required (NPSHr), we first need to clarify one basic concept: what is cavitation?

Simply put, when a pump conveys liquid, the local pressure at its suction side may drop. If it drops to the “liquid’s saturated vapor pressure” (for example, water at 20°C has a saturated vapor pressure of about 0.02MPa), the liquid will vaporize. This vapor forms small bubbles.

When these bubbles flow to the pump’s high-pressure zone, they collapse instantly. This collapse creates intense impact—like a tiny explosion. This process of “bubble formation + collapse + impact” is what we call cavitation.

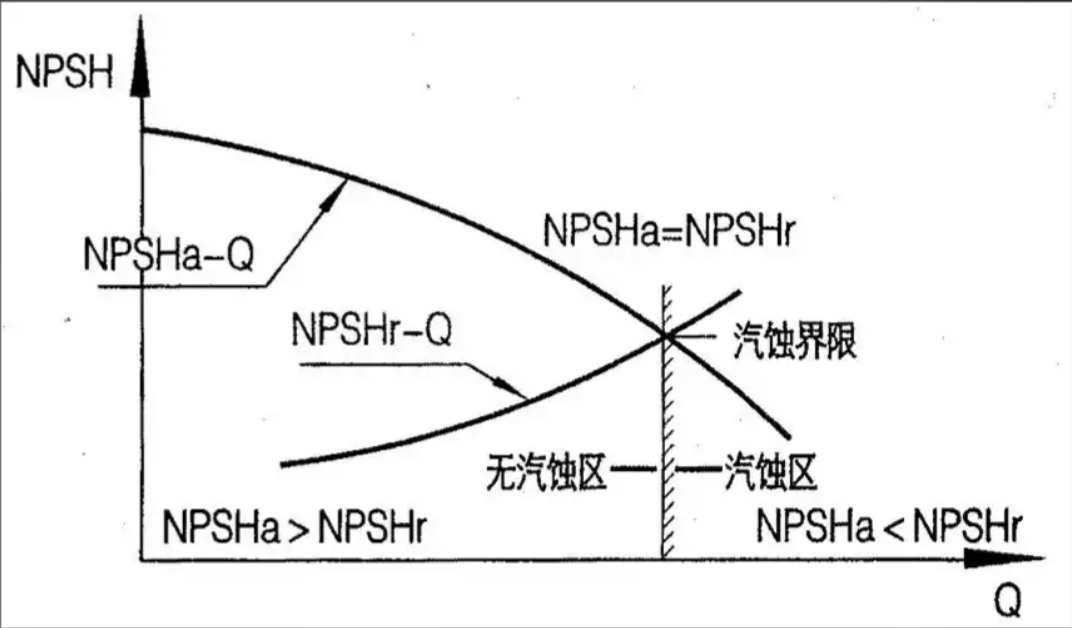

NPSH, in short, is a “safety buffer” against cavitation. These two parameters (NPSHa and NPSHr) are key to judging if a pump will suffer from cavitation.

I. What Are NPSHa and NPSHr, Exactly?

Think of these two terms as “supply” and “demand”—this makes them easier to grasp:

1. Net Positive Suction Head Required (NPSHr): The Pump’s “Minimum Need”

NPSHr is the smallest anti-cavitation buffer a pump needs to work safely. It is a fixed value for each pump.

- It depends on the pump’s design: things like impeller shape, suction channel structure, rotational speed, and flow rate.

- Pump manufacturers test and measure NPSHr, then list it in the pump’s technical specs.

- The core meaning: To avoid cavitation, the system must provide at least this much pressure buffer. A smaller NPSHr means the pump is more resistant to cavitation (it asks less of the system).

2. Net Positive Suction Head Available (NPSHa): The System’s “Actual Supply”

NPSHa is the real pressure buffer the pump’s suction system can offer. It depends on how you use the pump (your specific scenario).

- You calculate it like this: Take the absolute pressure at the pump’s suction side. Subtract two things: the liquid’s saturated vapor pressure, and the suction resistance loss in the pipeline.

- The result is NPSHa—the actual protection the system gives the pump against cavitation.

II. Why Do These Two Parameters Matter?

Cavitation is not a small problem. Once it happens, it harms the pump and your operations. NPSHa ≥ NPSHr is the only rule to prevent cavitation. That’s why these two parameters are so critical:

1. They Stop Equipment Damage

When bubbles collapse, their impact pressure can hit hundreds or even thousands of MPa. Over time, this does real harm:

- It erodes the pump’s impeller and casing. For example, a centrifugal pump’s impeller may get pitted—even holed—by this impact.

- It wears out seals. Mechanical seals, for instance, can fail due to the impact. This leads to medium leakage.

The result? Shorter pump life. A cavitating centrifugal pump may need a new impeller every 3–6 months. A non-cavitating one can have an impeller that lasts 3–5 years.

2. They Prevent Performance Failure

Bubbles take up space inside the pump. This disrupts normal liquid flow:

- Flow rate and pressure swing wildly. A pump made to move 50m³/h might only push 30m³/h. Its pressure can jump up and down, too.

- In bad cases, bubbles block the flow channel. The pump runs, but no liquid comes out—this is “flow interruption.”

For scenes that need stable flow (like oil and gas extraction or chemical processes), this failure stops production. It can even cause chain problems—like downstream equipment shutting down from lack of liquid.

3. They Reduce Safety and Energy Risks

Cavitation brings extra dangers:

- It makes loud noise (a sharp, rustling sound) and strong vibration. Over time, vibration loosens the pump’s base bolts. It can also leak pipeline joints or cause resonance in equipment.

- To get the needed flow, a cavitating pump may run at overload. This raises motor current, uses more energy, and can even burn out the motor.

III. Screw Pumps’ NPSH Advantages: Why They Beat Centrifugal Pumps

Screw pumps (especially twin-screw pumps) are positive displacement pumps. Their working principle is totally different from centrifugal pumps (dynamic pumps). This structure gives them big NPSH advantages—great for cavitation-prone scenes (like gas-rich media, high-viscosity liquids, or poor suction conditions):

1. More Stable Suction Pressure

Centrifugal pumps suck liquid by spinning impellers fast to create centrifugal force. At the impeller’s inlet, liquid moves fast and pressure drops—this is where cavitation often starts.

Screw pumps work differently. They use meshing screws to form sealed chambers. These chambers squeeze liquid forward. Liquid is pulled into the pump smoothly as the chambers expand. There’s no sudden speed change (unlike centrifugal pumps’ fast-spinning impellers). So suction pressure stays steady, and local low pressure (a cavitation trigger) rarely happens.

2. Lower NPSHr

Because their suction process is smooth, screw pumps have much lower NPSHr than centrifugal pumps. For the same flow rate and head:

- A twin-screw pump’s NPSHr might be just 1.5m.

- A centrifugal pump with the same specs may need 3–4m of NPSHr.

This matters for poor suction conditions: low tank levels, long pipelines with high resistance, or high-temperature media (which have high saturated vapor pressure). Even if the system’s NPSHa is small, screw pumps can still meet “NPSHa ≥ NPSHr”—so they rarely cavitate.

For example, when conveying gas-rich crude oil, centrifugal pumps may cavitate from local low pressure. But screw pumps keep running steadily.

3. They Tolerate Minor Cavitation

Centrifugal pumps have open impellers. Bubble collapse impacts hit the impeller directly. Screw pumps, though, move liquid in sealed chambers. These chambers buffer the impact of bubble collapse.

Even if a few bubbles form in extreme cases, they won’t erode the screws or casing. The impact on performance is small—no sudden flow stop, just slight flow changes.

4. They Handle Gas-Containing Media Well

Gas in media is a big cavitation cause. Gas gathers in low-pressure zones, making more bubbles. But screw pumps can handle media with 0%–100% gas content.

Twin-screw pumps, for example, use their sealed chambers to “wrap” gas and move it smoothly. Unlike centrifugal pumps (which can get “air bound”—a worse flow stop than cavitation), screw pumps cut down on cavitation from gas-liquid mixing.

Conclusion

NPSH is the “safety red line” for pumps. NPSHa is what the system provides; NPSHr is what the pump needs. The bigger their difference, the safer the pump.

Screw pumps stand out for cavitation resistance. Their positive displacement design, smooth suction, and low NPSHr make them more reliable than centrifugal pumps in tough scenes. That’s why they’re widely used in oil and gas, chemical, and other industries.

When choosing a pump, don’t just look at flow rate and head. First, calculate your system’s NPSHa. Then compare it to the pump’s NPSHr. This way, you’ll avoid pump damage from cavitation.